TWO

A New Kind of Start-up

Before you can understand how Ben, Jerry, Jeff, and their friends devised a new way of doing business, you must understand the times that produced them. They stumbled into their success by entering a new market niche at exactly the right moment. They called their ice cream “homemade,” but the industry named it “super-premium.” This kind of ice cream is usually sold in pints and has a high fat content. Premium ice cream is somewhat less rich and dense and is usually sold in larger containers. There are regular and economy versions of ice cream, too, but Ben and his customers didn’t see the point of them.

Ben & Jerry’s ice cream is about 16 percent butterfat, and the company does not allow much air into the mix. This makes the product dense. When properly frozen, it is as hard as a rock, which means that it is best enjoyed when partially thawed. It is more trouble to handle, more fattening, and more expensive than regular ice cream, but none of that mattered to Ben and Jerry in 1977. Only the taste mattered.

If the founders had been advancing a social mission back then, they might have hesitated to sell a product that is so high in saturated fat. But they didn’t give it a second thought. They were both twenty-six. They loved selling ice cream because it made people happy. If you gave it away, you could have a party anywhere, anytime you wanted, with almost anyone.

Those were the days when hippies were turning into capitalists. Old-fashioned ice cream parlors, bicycle stores, and head shops were opening all over the place. Many of them were in college towns like Burlington, where you could wear your hair long and smoke a joint on your lunch break. It might be hard to believe now, but most of the founders of these businesses, including Ben and Jerry, did not have a well-crafted “social mission.” In fact, many of them were ambivalent about politics because the mechanisms of electoral politics did not reflect their values. Ben and Jerry belonged to a diaspora of baby boomers who converged on Burlington in search of euphoria. They scooped ice cream for a decade before they started trying to change the world.

In the fall of 1977, a young man threw a dart at a map. The dart hit Vermont, so he and a friend got in their old car and drove there. People really did that back then. The young man made it to Vermont, but the car died soon afterward, so he hitchhiked into town a lot. One day, a beat-up old Volvo stopped and the driver gave him a ride all the way home, which was really nice of him. The driver was Jerry. He told the hitchhiker that he and his buddy, Ben, had just leased a gas station in Burlington. They were going to renovate it and sell food.

Ice Cream for the People

Ben and Jerry froze their butts off in that gas station all winter, demolishing, framing, and finishing. At night, they huddled around a wood stove in a poorly insulated house, living on crackers, sardines, and test batches of ice cream they cranked themselves. Their big idea was throwing candy, nuts, and other tasty stuff into the smooth chocolate or vanilla mix when the batch was partially frozen. This was a fairly new idea back then, and the results of their tests were often unbearably delicious. Of course, selling a frozen dessert in a place as cold as Vermont might not have been the smartest business idea, but they didn’t have an alternative plan.

Ben and Jerry liked having fun and helping others have fun. In the earliest days, the board that listed their flavors described them as “orgasmic.” Later, they switched to “euphoric.” The point was to have days full of positive personal interactions with employees and customers. They wanted to make enough money to live on while they enjoyed themselves, but they didn’t make much; in their first summer, they slept in the store. The following spring, to celebrate the anniversary of their grand opening, they spent a day giving away ice cream to anyone who showed up at the store, including dogs. Every day would have been Free Cone Day if they could have afforded it.

“We knew that we would only remain in business through the support of people in the local community,” Ben said in an episode of the television show Biography that first aired in 2006. “I liked the idea of free ice cream for the people.” And the Free Cone Day tradition continues today, although dogs are no longer served.

And the Free Cone Day tradition continues today, although dogs are no longer served.

Despite their images, though, Ben and Jerry were emphatically not hippies. They were smart and driven. They had been introduced to business by their families: Ben’s father was an accountant, and Jerry’s was a stockbroker. (Jeff’s dad owned a small clothing store.) Jerry’s original goal was to become a doctor, but all the medical schools he applied to turned him down after he graduated from Oberlin College in 1973.

Ben held a lot of different jobs after attending several colleges and dropping out of all of them. Before he went to Vermont he had been a potter, making stoneware bowls and pitchers. Some of Ben’s work shows his sense of humor. He made a soup tureen with hands clasped across the front of the bowl, as if they were holding a full belly, and a ladle sticking out under the cover like a tongue. The pottery didn’t sell, though, so he went looking for something else to do.

Ben was a brilliant marketer and salesman, with a fierce competitive streak. He had a magical ability to connect to his fellow baby boomers. He was a genius when it came to creating new flavors of ice cream, and he could be wildly funny, warm, and kind. People followed him. “A lot of people come up with crazy ideas,” said Jeff. “But Ben would actually go out and do the things he dreamed up. He would get me into unbelievable situations. I wanted to support his craziness.”

Jerry also enjoyed Ben’s crazy energy, but he wanted a quiet, orderly life. So Jerry decided to leave the ice cream business late in 1981, a few months after Time magazine began a cover story with the sentence, “What you must understand at the outset is that Ben & Jerry’s in Burlington, Vermont makes the best ice cream in the world.” Getting an endorsement from Time was a really big deal in the summer of 1981. Ben & Jerry’s had started selling ice cream in pints just a few months before the story ran, and they couldn’t keep up with demand. Jerry saw where the company was going, and he didn’t want to take the ride.

Getting an endorsement from Time was a really big deal in the summer of 1981. Ben & Jerry’s had started selling ice cream in pints just a few months before the story ran, and they couldn’t keep up with demand. Jerry saw where the company was going, and he didn’t want to take the ride.

Ben knew that he had a chance to make it big. But the work was hard, and neither of them had intended to become business executives. With Jerry leaving, Ben didn’t see the point of going on by himself. Then Ben delivered some ice cream to a local restaurant owner and artist and told him the business was for sale. The old restaurateur told Ben that the business was far too valuable to sell. He urged Ben to hold on to it.

Ben replied that he didn’t want to run a business. “I said, ‘Maurice, you know what business does, it’s harmful to the environment, it’s harmful to its employees,’” Ben said on Biography. “And he said, ‘Ben, if there’s something you don’t like about business, why don’t you just do it different?’ That hadn’t really occurred to me before.”

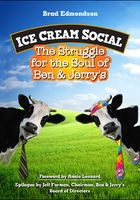

This photo of Ben (at left) and Jerry was taken in 1980 by Marion Ettlinger and has been printed on almost every pint container since.

Why Not?

The first thing Ben did after he decided to keep the business was to call Jeff Furman. Ben needed to turn Jerry’s half of the company into cash, so Jerry could leave with whatever he would have gotten if the company had been sold. Jeff suggested that Ben sell some of Jerry’s stock in a private offering to friends and family. He also drafted an agreement that would pay Jerry to stay on as a consultant, and he persuaded Jerry to retain 10 percent of the company’s stock.

Jeff’s next job was to find the money to expand the manufacturing operation out of a makeshift warehouse on Green Mountain Drive and into a real factory, one that was custom designed to produce ice cream with chunks in it. Commercial ice cream machines were designed to accept soft fruit, not hard chunks, so Ben & Jerry’s ice cream makers had to use trial and error to figure out how to keep the machines from jamming. Jeff also had to make sure that the company complied with all relevant rules and regulations, particularly with regard to a growing number of franchised ice cream stores. The company’s first independently owned Scoop Shop opened in Shelburne, Vermont, in the summer of 1981.

One early franchise owner remembers meeting Ben in those days. “His office was in a cold, grungy shed,” he says. “We were alone, except for a kid in the back who was hacking up Heath Bars with something that looked like a machete.” Heath Bar Crunch was the company’s first breakout success. Everybody wanted some.

The second thing Ben did was to look for a general manager. Chico Lager was running a popular nightclub down the street from the gas station. In 1981, Ben was thirty. Chico was two years younger, and Jeff was eight years older, but they had all grown up in similar families. Chico had once considered opening an ice cream stand in Burlington. And when Ben approached him, he was trying to sell his bar and get into something new. The more Chico learned, the more interested he became, and Ben soon hired him as general manager. Chico and his family bought some stock in the private offering. Jeff and Chico were added to the board of directors, and Ben, Chico, and Jeff became the management team.

Jerry moved away from Vermont in 1982 to follow his future spouse, Elizabeth, to graduate school in Arizona. Just before he left, though, Jerry cohosted the shop’s annual “Fall Down.” This was a street party featuring contests in stilt walking, apple peeling, and frog jumping—and, of course, there was lots of free ice cream. The highlight of the proceedings was when Ben appeared shirtless, wearing a turban and diaper-style pants, playing the role of Habeeni Ben Coheeni, the noted mystic. “He is carried out by his devoted followers,” Jerry said on Biography. “And Ben would go into this trance and would be laid across two chairs.” Jerry, who had taken a class on carnival techniques in college, would then bring the festival to its climax. “A cinderblock would be placed upon Ben’s ever-rounding bare belly, and I would lift a sledgehammer high above my head and bring it crashing down, demolishing the block.”

The poster for an early Free Cone Day featured two slogans: “Business has a responsibility to give back to the community,” from Ben, and “If it’s not fun, why do it?” from Jerry. Throwing parties by giving away huge amounts of inventory was not a full-blown social mission, but it wasn’t business as usual, either.

Ben & Jerry’s was ice cream for the people. And about the time that Jerry left for Arizona, the people developed an insatiable appetite. For a decade, the company often couldn’t make its product fast enough. Annual sales grew from just under $1 million in 1982 to more than $58 million in 1989. In their 1984 prospectus, Ben, Jeff, and Chico had guessed that their sales in 1989 would be $15 million. This posed what a business consultant would call a “high-quality problem.” As successful entrepreneurs, the guys needed to learn complex financial, legal, and management skills on the job as the number of employees grew from eighteen in 1982 to somewhere around three hundred in 1989, plus several hundred others working in franchised stores around the country.

For the three years after Jerry left, Chico focused most of his energies on protecting the bottom line. Ben handled sales and marketing, and Jeff did legal chores and whatever else needed doing. They managed the company in marathon monthly board meetings where, instead of voting, they discussed and compromised until the three of them agreed. Ben’s generous, unpredictable spirit sometimes made Chico’s job more difficult, but everyone was focused on the goal of managing the company’s runaway growth. The growth allowed them to ignore smaller problems. And like Jeff, Chico enjoyed Ben’s zaniness. He loved parties too, and Chico also recognized that Ben’s crazy ideas were often masterstrokes of marketing.

Social Stirrings

Ben & Jerry’s got serious about its “ice cream for the people” philosophy on April 26, 1984, the day the company made its first stock offering. That is when they really started sharing the company’s wealth with the communities that supported it. That was the day the company went public—but only Vermont residents could buy the stock. Ben said the sale allowed Ben & Jerry’s to give its best customers a piece of the action.

The company needed to raise $750,000 in equity to finance a $3.25 million ice cream plant in Waterbury, about twenty-five miles east of Burlington. Business was booming, and the prospects for expansion were bright. Or so the founders thought. Then Ben and Jeff tried to get a loan. Jeff remembers applying to dozens of banks before they found one that would even consider lending money to anyone who looked and acted like they did. And the bank officer added that he needed to see some equity first.

Ben came up with the idea to restrict the stock offer to people who lived in Vermont, with a minimum purchase of twelve shares at $10.50 apiece. Nearly everyone who heard the idea said that it was naïve and impractical. They told Ben that the stock offer could not reach its goal under those restrictions. But Jeff and Chico finally agreed to the plan because Ben would not back down. The fund-raising deadline was upon them. They needed to stop arguing and do something. Ben set the course, and they followed it.

The in-state stock offering was a classic Ben move, an idea that seemed crazy and exasperated his colleagues but then succeeded brilliantly. Chico and Ben made their pitches in rented conference rooms around the state. They sealed the deal by handing out free samples of ice cream after they finished talking. They easily raised the money, and that was just the beginning. The offer also generated a tremendous amount of publicity and goodwill. By the time it was done, nearly 1 percent of the households in the state owned shares of Ben & Jerry’s.

Restricting the offer to one state also made it unnecessary to register it with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which reduced the banking costs. Giving ownership to a large number of people, each of whom held a small number of shares, meant that Ben could get the money he needed while retaining firm control of the company. And the sale went far beyond the standard business practice of making small donations to community organizations. It was more like a merger with thousands of patriotic Vermonters who would hassle the corner grocer if he ever ran out of Heath Bar Crunch. It was the first time the company found a big way to make its financial, social, and quality objectives move forward together.

Creative thinking and flexibility saved Ben & Jerry’s more than once in those days. It came in especially handy when the company faced strong-arm tactics from Pillsbury, its chief competitor. Pillsbury, which spends millions on ads featuring a character called the Doughboy, owned Häagen-Dazs, the first super-premium ice cream in the United States. When Ben & Jerry’s started selling in Boston, Pillsbury told its distributors there that they wouldn’t get any Häagen-Dazs unless they agreed not to deliver Ben & Jerry’s.

Pillsbury’s move was blatantly illegal, but Ben and Chico didn’t have enough time or money to rely on the courts. So they came up with a dual strategy. First, they sent Jeff out to interview lawyers. Jeff found one he liked at Ropes & Gray, an elite corporate firm based in Boston. “As I was talking to Howie, he leaned back and put his feet up on his desk,” Jeff said. “He had a hole in the sole of his shoe. That sold me.”

Howard Fuguet specialized in antitrust law because he liked working with entrepreneurs. “I had done quite a bit of work representing underdogs,” he said. “I was intrigued by Ben & Jerry’s, and I thought that we could win this.” Howie became the company’s lawyer, an important advisor to the board of directors, and, as the years went by, a storehouse of institutional memory.

Ben and Chico also crafted a non-legal strategy, in line with their philosophy of cultivating direct, personal relationships with customers. They put notices on their pints inviting customers to join a campaign called “What’s the Doughboy Afraid Of?” They mailed out packets with bumper stickers and form letters customers could send to Pillsbury’s CEO. They also flew Jerry to Minneapolis to stand in front of Pillsbury’s headquarters with a picket sign. “I was very much in favor of this,” Howie said. “I could see the marketing value of the lawsuit. I might have asked them to tone down a couple of their slogans, but it was a very interesting project.”

Jerry always gets a laugh when he tells the Doughboy story in speeches now, mostly because he portrays himself as hapless and nutty. “Nobody had any idea of why I was there,” he said at a talk at Cornell University in 2013. But that isn’t quite true. Ben and Chico made sure that a photographer for the Minneapolis Star Tribune was there. The Associated Press picked up the story, and it ran all over the country.

The Doughboy campaign generated an avalanche of positive publicity for Ben & Jerry’s, and it put so much pressure on Pillsbury that the big company was forced to back off. It also set a pattern the company would use, with spectacular results, for decades. Instead of doing traditional advertising or marketing campaigns, Ben & Jerry’s would take their product directly to people. It would market to taste buds through sampling, and also to an ordinary person’s sense of fairness and justice by taking on social issues.

In 1984, Ben & Jerry’s asked the public to protest Pillsbury and Häagen-Dazs for illegally threatening the company’s survival. Jerry’s visit to Pillsbury’s headquarters in April was widely covered by the press.

Ben & Jerry’s commitment to linked prosperity deepened a year later when Jeff and Howie led the company through a national stock offering. Again, the company went directly to its customers first. It put a notice on each pint that encouraged customers to “Scoop Up Our Stock,” with a toll-free number to call for a prospectus. “It was an unusual move,” said Howie, “but once the Securities and Exchange Commission people understood it, they just laughed and said, ‘Why not?’ We kept trying to come up with things for Ben & Jerry’s that were a little novel. I regarded it as a challenge, and they encouraged me.”

As Ben, Chico, and Jeff worked on the prospectus for the national stock offering, they realized that they needed to tell potential investors exactly how much of their money the company planned to give away. Ben had been giving larger and larger cash contributions to local groups, while Chico had been trying to keep the giving at around 5 percent of pretax profits. So they created the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation, an independent nonprofit organization funded by the company. Its goal was to support projects that were unlikely to be funded through traditional sources. The projects they were looking for would be models for social change, ideas that enhanced people’s quality of life, and community celebrations. Jerry agreed to be the foundation’s president. Jeff was the second board member, and Naomi Tannen, who had owned Highland Community, the school where Ben had met Jeff, was the third.

Ben endowed the foundation with fifty thousand shares of his stock, which was a little less than one-tenth of his equity in the company. He wanted to set the company’s annual contribution to the foundation at 10 percent of pretax profits, or double the percentage that Chico had tried to maintain. Chico replied that giving this much away would make it impossible to fund future expansions without more stock offerings, which would further dilute Ben’s ownership. The underwriters added that investors wouldn’t buy into a company if it gave away so much cash, because that would reduce dividends. After a lengthy argument, Ben compromised on 7.5 percent of pretax profits, or nearly four times the national average.

Ten percent would have been fine with Jeff, though. Like Ben, he was enthusiastic about building a different kind of company. Jeff lived in Ithaca, a six-hour drive from Burlington, and he was a consultant, not an employee, so he was not involved in many of the day-to-day decisions. Jeff’s work duties were not as intense as Ben and Chico’s were. But as a board member and key advisor, he had a lot of influence. And Jeff often says he always looks for ways to make things more interesting, more political, and more fun.

Decisions and Consequences

The construction of the Waterbury plant went fairly smoothly because the guys got a gigantic lucky break. One day in 1984, Merritt Chandler, a recently retired business executive with deep roots in Vermont, walked into the office to get a prospectus for the in-state stock offering. Ben and Chico were just beginning to plan the plant’s construction. In the best tradition of entrepreneurs, they were attempting to do a job for which they had not been trained. But building an ice cream plant is difficult, and this plant would be especially tough. It was going to make flavors with irregular-sized chunks, and those had never been produced in large quantities before. And the company was also going to start making its own mix, the smooth ice cream base, which meant that it was going to start mixing cream, sugar, and other ingredients itself.

Ben was “creative, bright, and a quick study, but he really didn’t have the vaguest idea of what he was getting into,” Merritt said years later in the employee newsletter. So Merritt, who had built plants for Xerox, offered to help. Within a month, he and Ben were working full time to manage the construction project. Merritt’s engineering expertise was essential, and he also became an important role model for old-fashioned values like mutual respect, restraint, and discretion. These qualities are essential to managing a larger business, but they did not always come naturally to the employees or board of Ben & Jerry’s, many of whom were proud to describe themselves as hippies, radicals, and misfits.

The plant’s opening in the summer of 1985 was a major turning point for Ben & Jerry’s. With close to a hundred employees in the building, Ben and Chico had to delegate authority, so they hired managers to direct sales, operations, and personnel. The atmosphere became chaotic as growth accelerated, because the managers didn’t always agree or even know what others were doing—and also because the company’s founder and CEO kind of liked things that way. Many companies develop a culture that mimics the personalities of their leaders. Everyone who worked with Chico says that he was a stable, no-nonsense kind of guy who liked a good joke. But Ben could be abrasive, and his wacky sense of humor sometimes baffled people. He had a habit of changing his mind without explanation, which made planning impossible. He was also maniacal about quality, and he worked very, very hard.

At the beginning of 1985, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream was sold in Boston and New England, and the company had just started delivering to New York City. Other super-premium brands were emerging, and the board was eager to get into new markets before they did. Waterbury had quadrupled the company’s production capacity to about eight hundred gallons of ice cream per hour. So the company’s first sales director negotiated a distribution deal with Dreyer’s, a California business that made premium ice cream and was looking to expand eastward. Dreyer’s starting carrying Ben & Jerry’s across the country in the summer of 1986.

The Dreyer’s deal was an example of a sensible decision that also became a point of no return. It gave the company the ability to compete on a national scale with Häagen-Dazs, which was the only national super-premium brand in 1986. Without it, Ben & Jerry’s would probably have remained a smaller, regionally focused ice cream business, with a much smaller impact on the world. But the deal also came at a price. By giving up control of the network that delivered its product from the factory to stores, Ben & Jerry’s became dependent on others for its growth. The company also became more vulnerable to buyouts and mergers among distribution companies.

The introduction of a salary ratio was another casual decision that had huge consequences. One day in 1985, Jeff suggested that Ben & Jerry’s borrow a tactic from the Mon-dragon Corporation, a confederation of worker-owned cooperatives in Spain. Mondragon’s worker-owners determined the salaries of their managers by voting, and Jeff had read that the average ratio they settled on was three to one. In other words, the highest-paid Mondragon employee could not earn more than three times as much as the lowest-paid employee did.

Ben liked the idea of a salary ratio that was five to one. Chico hated it for several reasons, chiefly that the comparatively low top salaries would make it harder for him to hire talented managers. But even after the national stock offering was successfully concluded, Ben owned a little less than one-third of the company’s shares, far more than anyone else, and he was still the president and CEO. Ben didn’t throw his weight around often, but in this case he did. Ben announced that the company would follow a five-to-one salary ratio and, as one might expect, the line workers loved it. So did the media. Of course, every business school professor Jeff talked to told him that he and Ben were out of their minds. But with a new plant to open, new markets to enter, and interesting offers coming over the phone almost every day, there wasn’t much time to debate philosophical questions.

In hindsight, it’s easy to see the turning points. The stock offerings, the distribution deal, and the generous annual contribution to the foundation set the company’s directions in finance, operations, and philanthropy. In the early years of public ownership, being controlled by shareholders wasn’t much of a problem because Ben, Jerry, Jeff, and their Vermont fans controlled the majority of shares. But as the company grew, so did the number of owners, and balancing their needs with the founders’ wishes became increasingly complicated.

The salary ratio shaped the company on a different level because it cut across every category of the business. Within the company, it caused endless arguments that sharpened the social mission, and it also defined the company’s public image. It guided the company’s fortunes, for better and worse, over the next nine years.

The Return of Jerry

The national stock offer had made Ben a multimillionaire at age thirty-five—at least on paper. But he was still working all the time. Eighty hours a week was not unusual. Ben’s friends say that he has an exceptional ability to stay focused on a task and get to a goal. He had almost sold the company in 1982 because he didn’t really want to be a business executive. And he still had the desire to get out in 1985. This time, he could have walked away with enough money to retire. But he didn’t, because by 1985, Ben also had a compelling vision for his life’s work. He was getting tired, but he was also determined to show the world that a socially responsible alternative to a traditional business could work.

Fortunately for Ben, one of the people he could turn to for help in 1985 was his best friend. Jerry and Elizabeth returned to Vermont just as the Waterbury plant opened, and Jerry started doing various jobs for Ben & Jerry’s. He would pull an occasional shift on the production line, getting reacquainted with the employees. He also began attending board meetings. Jerry did not have an official vote, but that didn’t matter much, because the board hardly ever voted. Ben, Jeff, Chico, and everyone else in the company were immensely relieved to have Jerry back in the mix.

Jerry was Ben’s other half. Ben cultivated a laid-back public image, but when he was running the business, he was a taskmaster and a perfectionist who had the annoying habit of changing his mind without warning. “Working with Ben was, in plain English, a pain in the ass,” wrote Chico in his entertaining memoir of the early years, Ben & Jerry’s: The Inside Scoop. “Ben was usually so single-mindedly convinced that he was right about something that he often didn’t even acknowledge the legitimacy of alternative points of view.”

Ben could burn people out. But Jerry was a peacemaker, calm and gracious and nurturing, and no one ever seemed to get mad at him. The two men have a deep friendship. They depend on each other, and they were surprising but perfectly matched business partners. They were like the raisins and pecans they mixed into chocolate ice cream to create Dastardly Mash, one of their first successful flavor combinations. No one else would have thought the combination would work, but no one could resist it, either.

Jerry led the founding board of the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation, and with Jeff and Naomi Tannen, he set its direction. The foundation’s first gifts in 1986 included a program at Goddard College that aided single parents on public assistance, a basketball court and ice rink in Waterville, Vermont, and other grants totaling $153,000. The foundation also launched a nine-month search for the best community celebration in the Northeast, with a first prize of $15,000. This was as much as they gave any individual grant. The foundation’s big idea was to give small, targeted sums for groups that would not ordinarily apply to foundations, in hopes of maximizing the impact on actual lives.

The gifts fit with the company’s policy of putting people first. They were good for business, too. Free publicity and word-of-mouth recommendations from passionate customers were more than enough to keep the growth train rolling. The board found itself managing a rapidly expanding food business whose identity was closely tied to its two charismatic founders, both of whom were passionate about social justice, inclusiveness, and grassroots decision making. They were not as passionate about the nuts and bolts of the ice cream business, however.

Ben and Chico encouraged employees to solve problems themselves, and the employees often found unusual solutions. “We didn’t have an employee newsletter, and we needed one,” said Lisa Wernhoff, who worked in the design department. “So a bunch of us started writing up items we thought were important. Once a month we would get together after work with scissors, tape, and a margarita blender. The later it got, the more risqué our jokes got. Around three in the morning, someone would go to the main office to photocopy, collate, and fold it. It was important to put it on peoples’ desks before the day started, because we weren’t supposed to do it during working hours.”

As the Waterbury plant settled into a semichaotic routine, Ben and Chico reached an informal understanding. Ben would leave the day-to-day questions of running the business to Chico and the managers so that he could focus more on longer-term, strategic issues. Ben also said that he wouldn’t mind if the company’s growth slacked off a bit, because this would give the company’s managers and employees time to grow into their new, bigger jobs. But, Chico writes, Ben had a hard time staying out of things. When he saw something that wasn’t up to his standards, like a broken freezer door that wasted a lot of energy, he flew into a rage and insisted that it be fixed, now. When he saw an opportunity to go into a new market or was inspired to create a new flavor no one could resist, he plunged in. Sometimes Ben was in, and sometimes he was out, and no one could predict when he would change direction.

The company was struggling to make enough ice cream to meet demand. The factory was too small, even on the day it opened, and the complications of adding candy, fruit, and nuts to the mix meant that many batches didn’t work. The production lines ran around the clock, with employees routinely pulling twelve-hour shifts, and accidents were a mounting problem. Ben, Jeff, and Chico found themselves running a fundamentally different kind of company. They were constantly hunting for experienced managers who were capable of handling the business issues caused by runaway growth. But they also needed managers who were inspired by the company’s unconventional business practices—so inspired, in fact, that they were willing to take a substantial cut in pay. The company’s search for mission-driven executives would continue for the next decade, and it would lead them to places they never thought they would go.